*EIN News

In the frigid North Sea, 90 miles off the coast of Norway, oil giant Equinor has developed one of the biggest projects in its 50-year history—a 300-foot-tall platform called Johan Sverdrup, which when it hits peak output will be gushing 750,000 barrels of oil per day. The field, containing an estimated 2.7 billion barrels, will flow for decades, generating copious cash for Equinor, which is 70% owned by the government. Norwegians are of two minds when it comes to oil. It’s made them among the richest people in the world, filling up the coffers of their $1.2 trillion sovereign wealth fund. But these environmentally conscious Scandinavians are also sheepish about its environmental impact. The company changed its name in 2018 from Statoil to Equinor (i.e., Equity+Norway), and new CEO Anders Opedal has pledged to make it carbon-friendly as the first “net-zero” oil company by 2050.

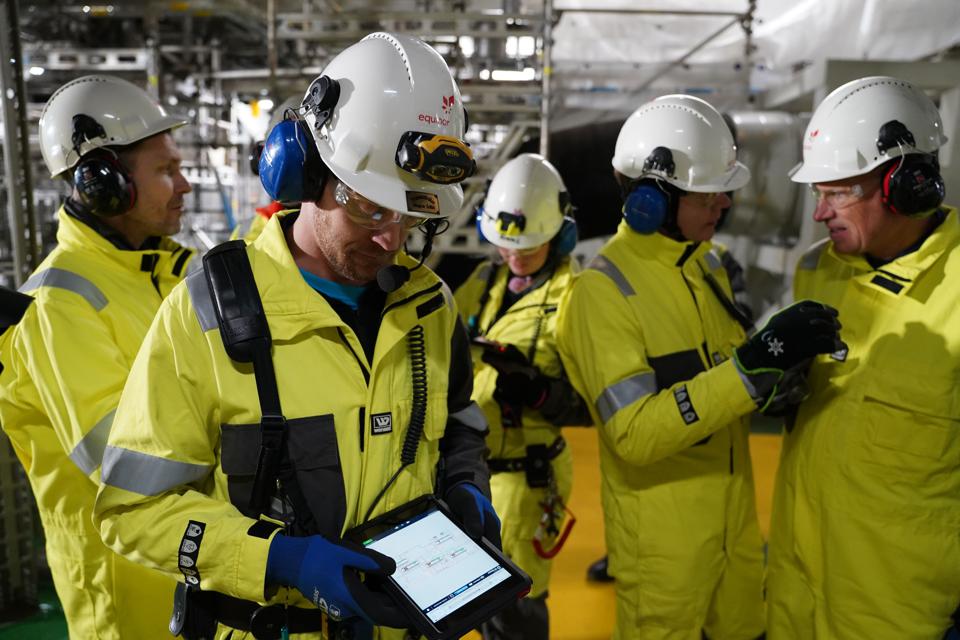

In the interest of optimizing efficiency, Equinor has outfitted Johan Sverdrup with thousands of sensors monitoring everything from how much oil is flowing through pipelines, how fast new wells are being drilled, to how much diesel fuel the facility is consuming. All told, Johan Sverdrup’s sensors generate the equivalent of 15 high-def video streams, which are transmitted continuously to Houston-based startup Data Gumbo, which encodes the most important data onto a proprietary, immutable blockchain ledger called GumboNet.

“We use data from the field to confirm transactions, and we store that data in the chain. Customers manage the distributed ledger,” explains Data Gumbo CEO Andrew Bruce. “No party can change any part of the transaction that provides the trust. There’s not two versions of the truth.”

The platform thus enables dozens of “smart contracts” between Equinor and its army of suppliers. “In the old days it would take weeks to reconcile orders with records, weeks more for contractors to get paid,” says Bruce. Now a smart contract can be programmed to trigger payment to a drilling contractor when a sensor on a rig indicates that their drillbit has reached a certain depth. Contractors like Baker Hughes “get paid sooner and for the correct work,” says Bruce. This gives Equinor leverage to negotiate for cheaper contracts, and to reduce both its ranks of back-office bean counters and working capital. Equinor figures that in its first year of operations Johan Sverdrup saved $20 million thanks to Data Gumbo.

AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

Data Gumbo has 20 customers so far. Equinor, its most bullish adopter, began testing the GumboNet in 2019 with simple pilot projects like monitoring trucks hauling water for its U.S. shale fracking operations. It has since announced plans to deploy its platform at ten big projects, including its new Dogger Bank offshore wind project (set to be the world’s largest). It has also acquired an equity position in Data Gumbo, investing $6 million into the Houston-based company. And it’s not alone, Saudi Aramco, the biggest of Big Oil, has invested $4 million, and is considering deploying GumboNet for some of its own operations. Total fundraising is $20 million. “We have to show a compelling cost saving,” says Bruce. “The oil crash was good for us in that it showed the status quo is no longer good enough. Companies have to reduce expenses.”

And there are even broader implications here—for what is shaping up to be the grand transition to lower-carbon energy sources. It’s just a matter of time before all sorts of industrial companies are using blockchain networks to monitor and tabulate their carbon emissions. “If you’re measuring the utilization of machines in the field, and know their efficiency and fuel usage, you should be able to provide a carbon footprint,” says Bruce, who is already working with the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board on a program to certify all-important ESG scores (environmental, social and governance) based on data they already collect. “Blockchain is the best source of very real, clean data. It’s not based on estimates—it’s based on fact, because everyone is paying bills off of it. So you can deliver an ESG score to investors with certainty,” he says. “It’s an elegant solution that falls out for free.” Well, maybe not quite free. Data Gumbo gets paid according to how much customers use the network.

Equinor is thinking creatively about how to get more out of blockchain applications. According to a spokesman, as society grows ever more serious about reducing carbon emissions, there will be greater requirements for certifying the carbon content of energy supplies: “You could some day in the future track carbon molecules” all the way through the petroleum value chain. “You can’t improve what you don’t measure.”

Sure there’s some challenges: It’s far easier to integrate a blockchain-connected sensor mesh onto a new field than retrofit an old one. And drawbacks: More automation and efficiency requires fewer workers. Plus some service companies won’t like the greater scrutiny of having their every action recorded on GumboNet. The upside for Data Gumbo: “Once an anchor tenant is in place, it’s hard to dislodge a company like ours. We have a prebuilt network and new customers can just get on.”

Matchless topic, very much it is pleasant to me))))